The Fables of La Fontaine

Do you have a river of your dreams, a place that comes first to your mind whenever you think “flyfishing?” It may be a memory snapshot of somewhere you’ve already been or a mental compilation of everything that is the best in our pursuit. Picture it for a moment, what’s it like?

What size, with what backdrop, in what country? Does it have long smooth glides where rise-rings take forever to dissipate, or is it fast and boisterous, with plenty of big rocks for rainbows to sit against? Is it an easy ego-pampering water à la Timaru Creek or a fair dinkum test like the lower Tongariro where massive browns regard you with contempt? Whenever I closed my eyes I always saw my river clearly but only this spring I realised that it actually exist, and that it has a name. I also got to fish it for all of three days. Talk about vision becoming a reality!

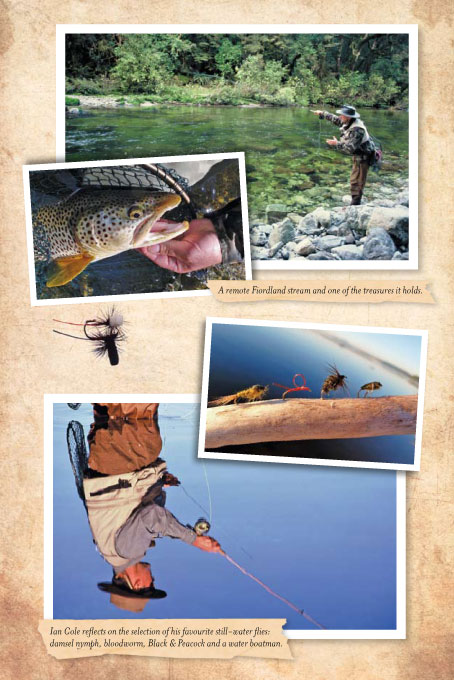

The river is called La Fontaine and it seeps out of the swampy paddocks on the New Zealand’s West Coast, two hours north of the glaciers, near the farming settlement of Hari Hari. It’d be tempting to think that it was named after the writer Gary LaFontaine who, as one journalist noted in Gary’s 2002 obituary, “was a flyfisherman—in much the same way Albert Einstein was a mathematician.” You may have come across his books – Trout Flies: Proven Patterns, Caddisflies, and The Dry Fly: New Angles – they are classics in their field. But it’s more likely, certain in fact, that the river carries the name of another scribe, the Frenchman Jean de La Fontaine, a conjurer of magic and fables. For a dream river such association seems particularly fitting.

I’d been meaning to explore it for years and never had but this time we’d finally set a date and made it happen. My fishing compadre David Lloyd flew in from Hong Kong and one sunny November day we set off in my camper, from Wanaka and up the coast. By that time we’d already had a week’s fishing on our favourite River X, hard but rewarding, and it was the most memorable trip ever (sorry mates, no GPS coordinates here.) Sight-fishing to eager browns, the solitude and the luxury of having the river to ourselves had raised our standards, honed the expectations. Thus we arrived in Hari Hari a little too cocky perhaps, two self-professed experts ready to kick butt. The La Fontaine browns would see to it that we did not delude ourselves for long.

La Fontaine is a river-size spring creek, with fat weed beds waving in the current over clear patches of light gravel and sand, all of which makes for rather good spotting. David and I delight in sight fishing, now almost to an exclusion of any other style, and the “See no fish, cast not” adage has become something of our modus operandi. We are happy to walk for miles just looking for the moments of magic this particular kind of voyeurism affords, knowing that to see even one fish react to a fly – to see it take, inspect or refuse – is an experience far more intense and memorable than catching half a dozen fish blind.

La Fontaine is a river-size spring creek, with fat weed beds waving in the current over clear patches of light gravel and sand, all of which makes for rather good spotting. David and I delight in sight fishing, now almost to an exclusion of any other style, and the “See no fish, cast not” adage has become something of our modus operandi. We are happy to walk for miles just looking for the moments of magic this particular kind of voyeurism affords, knowing that to see even one fish react to a fly – to see it take, inspect or refuse – is an experience far more intense and memorable than catching half a dozen fish blind.

Maybe it’s because we’d both done our river mileage, flogging the water without seeing the fish first, or perhaps it is a residue of my years as a fishing guide. For a guide, watching his clients fishing blind can be intolerably boring which is why we so insist on finding the fish. Spotting makes a guide feel useful and engaged, a part of the adventure. All other alternatives are grim by comparison. Consider the renown Scottish gillie who was asked what was the single most important skill for a career fishing guide. After scratching his beard in deep thought he replied: “I’d have to say it’ll be the ability to yawn with your mouth shut.”

Continue reading …

We also stray into river conservation issues, it is difficult not to these days. Ian is a vocal activist for water quality and he will also appear in our upcoming documentary The Trout Heaven and Hell.

We also stray into river conservation issues, it is difficult not to these days. Ian is a vocal activist for water quality and he will also appear in our upcoming documentary The Trout Heaven and Hell.