To Jennifer, for being you . . .

‘Study to be quiet.’ Isaac Walton

‘Do not burn yourselves out. Be as I am — a reluctant enthusiast . . . a part-time crusader, a half-hearted fanatic. Save the other half of yourselves and your lives for pleasure and adventure. It is not enough to fight for the land; it is even more important to enjoy it. While you can. While it’s still here.’ Edward Abbey

‘Let your boat of life be light, packed with only what you need — a homely home and simple pleasures, one or two friends, worth the name, someone to love and someone to love you, a dog, and a pipe or two, enough to eat and enough to wear, and a little more than enough to drink; for thirst is a dangerous thing.’ Jerome K. Jerome

‘Your casting is poetry in motion, mine is more like punk rock.’ Jennifer White

Prologue

The big trout held just under the tongue of current breaking off an island-like boulder and from where we stood it was nearly invisible, camouflaged beneath the liquid greenstone of the river frothed with whitewater. Only the sway of its tail gave it away, and only when a brief window of smooth water passed over it, which was how I first sighted the brute.

‘There is a good fish just down and left of that boulder,’ I said to my companion Frank Mosley, and pointed to it with my fly rod.

Frank couldn’t see it, but this was to be expected. Unless you’ve trained your eyes to spot New Zealand trout, you are likely to miss all but the most obvious ones. Frank was from Montana, accustomed to fishing water rather than individual trout, though to his credit it was tough to see fish here in the Reefton backcountry. The ostrich-egg boulders that cobble the riverbeds are bone-white and, in bright sunlight, as hard on the eyes as the blinding glare of a glacier.

‘Trust me,’ I said. ‘There is a fish there alright, and a big one too. Just cast a metre up and left of that boulder.’

Frank did, even if he was not entirely convinced. His cast was accurate enough, but for a long, suspended moment nothing happened. He lifted the rod and the line seemed snagged.

‘Damn, I caught the botto. . .,’ he said, but then the bottom near the boulder exploded with a fury of spray. The big trout was airborne above it, shaking its head from side to side, its arched wet body glinting gold as it caught the sunlight. The fish bounced off the water a couple of times, then shot downstream, like a soft lithe torpedo and a contradiction to all laws of fluid mechanics.

‘Oh, my Gawd,’ Frank’s voice was an octave above his usual baritone. ‘Did you see THAT? It’s a monster!’

We followed at a run, rod held high but bent into a deep C, Frank’s eyes fixed at the end of his line. He seemed in a trance, ready to walk on water. Well, almost. He was fit and nimble for his mid-sixties, but a few times I had to catch and steady him as he stumbled over rocks he did not see. The fish was taking us down the river and we crossed and recrossed the tumbling current, wrestling with it, tripping and fumbling on the slippery bottom, gaining some line, losing it again, but at all times keeping it taut like a guitar string.

Twice Frank was down on his knees, flailing, on all threes but with his rod arm steady and strong. With a pang of dread, I saw where the fish was heading: a mother of all logjams in a pool below us. If he went in there, into the debris of past floods, we would never get him out.

But then, in the eye of calm below the rapids and just short of the logjam, I finally netted the fish and he was just shy of the magic 10 lbs that is the hallmark of a trophy. Frank got his pictures and we released the fish immediately. He was a magnificent trout in its prime, with a fiercely hooked lower jaw, muscled body and a glistening skin that seemed too tight for it.

He was just as spent as we were, and he nosed into a rock in the slack water right at our feet, and for a long while all three of us just sat there in absolute stillness, catching our breaths, the only sound the murmur of the river.

Then I heard that Frank was sobbing — and trying to cover it with laughter. He rubbed his eyes with his buff, his hands trembling. ‘The goddamned river water got into my eyes,’ he said, but he was fooling no one.

I smiled and said it was a really good fish, the kind you’d expect out here.

‘No, no, you don’t understand. I’ve been fishing all my life, since I was big enough to hold a rod, and this is the best trout I have ever caught,’ Frank cut in. ‘Where I live you cannot even buy this kind of experience any more, no matter how much money you have.’

He fell quiet and withdrawn afterwards, taking time to absorb the experience, and he did not want to to fish anymore that day, as if not to dilute the quality with repetition or numbers.

On the way back down the river he said:

‘You’re probably spoilt because you can have this anytime you want, but for me this one fish was worth coming all the way down here for. Mountain climbers go to the Himalayas for the best there is, fly fishermen come to New Zealand. Today, I bagged my personal Everest.’

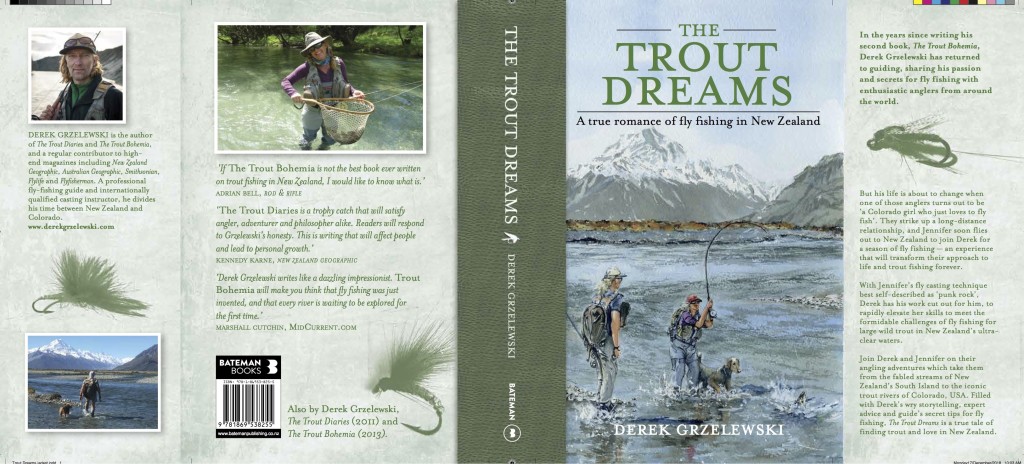

Yep, you’ve guessed it: I was back to guiding and it happened in a most roundabout kind of way. Ever since The Trout Diaries was published in 2011, and even more so after The Trout Bohemia two years later, I’ve been receiving a steady flow of emails from the readers, an unexpected perk and delight from writing books. (When you write for magazines, whether local or international, as I had for the past two and a half decades, most commonly the only reader feedback you get is when you make a mistake — a trivial gaffe or a factual error — which certain kind of people just love to point out, though rarely in a constructive or humorous way.)

But these letters were different. Often they were deeply personal since, at its best and true, fly-fishing is a profound and intimate experience, and, yes, they were also filled with accounts of the writers’ own river exploits, both happy and less so, and they carried a common message that somehow we fished in similar ways and for compatible reasons, responding as if by resonance to the call of the trout waters. The authors of the emails wanted me to know that they got what I was trying to convey in my own writing about the magic of fly-fishing that defies explanations and is so hard to put into words, or, as Hemingway said, it’s just plain ‘too swell to talk about’.

More often than not, the emails would conclude with something like ‘I wish we could go for a fish together one day’ to which I routinely replied that I was busy but my guide friends, some of whom were featured in the books, could certainly help with that.

Then, one time, after an email exchange with a particularly insistent reader, I thought ‘why the hell not?’ I was about to leave on a week-long trout hunt and so was he, and in the same region. The fishing was good, the forecast even better. Our dates matched; it was too much of a coincidence.

We met, and fished, and camped, and talked long into the campfire nights about all manner of things. For the first time guiding did not feel like drudgery to me, an exercise in miracle-making against all odds and lack of even the most fundamental skills that needs to be tactfully endured at the time, and later washed off with copious amounts of whisky.

To the contrary, the outing turned out to be one of the most memorable fishing trips I’ve ever been on largely because I’d changed the way I guided — changing not the what but the how. The mechanics remained the same, but the attitude was different, and the attitude is like tinted glasses: it can darken or brighten how you see things and colour your perception. And so instead of trying to guarantee saleable goods — usually trout and ideally big trout and plenty of it — in the process attempting to control the uncontrollable and getting stressed about it all, I began to guide the way I fished for myself.

Walking the rivers, looking for and finding fish, taking shots at them to the best of my ability and seeing how this played out, celebrating when it did, laughing when it didn’t. Essentially, going fishing with clients as I would with friends, just giving them all the opportunities. This made for a much more relaxed atmosphere, reducing the pressure that so often both the guide and the guided angler put on themselves. After all, fly-fishing was meant to be fun, right? Wasn’t this one of the reasons why we did it?

In a way then, this was a return to what fly-fishing was supposed to be, at least in its pure and true form, before it has been subjected to rampant commercialisation which has turned trout into a commodity to be advertised, acquired, shown off and bragged about. As John Gierach wrote with his trademark sarcasm, the kind of people he’d want to guide didn’t usually want a guide or to be guided. Somehow, though, the second time around I managed to find the middle way of doing what I loved without pimping it out. I guess my books have acted as a filter and a declaration of intent, style and approach so that I did not attract wannabes who just want to catch big fish only to post pictures of them on Facebook but rather true anglers who engage with the world of trout through fly-fishing and on deeper levels, more like my own.

This change in attitude of treating guiding not as a job but as a way of taking new friends out fishing and helping to make things happen for them took time to grow and evolve. It has been both radical and revelatory, although I cannot claim to be the originator. I had a friend who was a mountain guide, one of the most experienced in the country. We used to fish and ski tour together a lot, and one time he told me that for him it did not make any difference whether he was guiding a client or climbing with a friend; he was getting just as much enjoyment out of both.

Anton died guiding Aoraki/Mt Cook some years ago, but his words have stayed with me ever since. Finally, I think, I too got what he was trying to tell me. Perhaps I’d grown up a little as well.

And a good thing I did, because otherwise I’d might have never met Jennifer.

A few years had passed since I lived and wrote The Trout Bohemia. Ella, the book’s main protagonist and its chief villain, was long gone. Last time I heard anything about her she was studying tango in Buenos Aires and no doubt had taken her demons there with her. After the endless dramas and emotional fireworks of trying to be with her, I delighted in silences and the peace that followed after she was gone. They were like a clearing after a storm, quiet enough so that I could hear the sound of rivers again, and so I wrote, and I fished through the seasons and ski toured the winter backcountry with my dog Maya and only a few of the closest friends. I thought if this was all that there ever was, it was fine by me and certainly enough and fulfilling. But Life does not let you idle for long and new events of the highest magnitude were already approaching my horizon even if I could not quite see them yet.

Like Frank and so many others, Jennifer wrote to me asking about fishing in New Zealand. She had read my books and she was intrigued by them and by the challenge of trying to catch those almost mythical antipodean trout, the style we favoured and its self-imposed purity.

‘I’m a simple Colorado girl who just loves to fly fish and doesn’t care about catching,’ she wrote, and I thought ‘Yeah, right. They all say that, until you get them to the river and point out trout bigger than anything they’ve ever seen.’

All this was happening during the busy peak season and so I wrote back to her with some hasty suggestions, all of which were long-shot and rather expensive options, at least a year away, and so I fully expected not to hear back from her. Surprisingly, she replied the very next day; she was positively dreaming about New Zealand trout. I wrote back, and so did she again, and before long we had a conversation going, then daily messages, then the first phone call and a video chat.

I was taken by her enthusiasm. She had never fished in New Zealand before, but she’d clocked an impressive fly-fishing mileage elsewhere, as diverse as it was exotic. British Columbia steelhead and salmon, Christmas Island bonefish, tarpon and snook in Mexico and Florida, redfish in Louisiana, and trout, wherever she could find them. In her family, fly-fishing went back four generations and she lived near one of the best trout waters in America: the Fryingpan and the Roaring Fork rivers near their confluence with the upper Colorado.

Her father Brit, retired to a riverside property, fished most days and when he didn’t he tied flies, exquisitely crafted and just as innovative, and they spent many happy river days together, reunited by their mutual passion for trout after years of estrangement and living in different countries and cultures.

One thing too was clear, that unlike so many fishing wives, girlfriends or daughters dragged into the sport against their will but enduring it just to please their loved ones, Jennifer’s interest in fly-fishing was pure and independent, unadulterated by influences and peer pressure.

‘I love it all, all aspects of it,’ she told me in one of our earlier conversations, ‘the fishing, the fish, the bugs, messing about with the gear, thinking about it, reading about it, dreaming about it. Fly water is where I’m the happiest, and all I need to know is that there are fish in it and that there’s possibility of catching some of them.’

I was intrigued. The season flew by — the cicada summer, autumn mayfly hatches, the first spawning runs of early winter — and my days were often long and demanding. Yet every time I got home, every morning I’d get ready to head out to the river again, there would be a little message from Jennifer — a note of few words, a picture or an e-card, a link to a song or a movie clip, a joke or a flirt.

Before she went fishing for steelhead on the Dean River with her father, for a week at a remote fly-in camp and totally out of cell and Wi-Fi range, she mailed me a pack of home-made postcards with a detailed instruction what to open on what day and in which order. Thus, in our communications, she never missed a day and, as I replied in kind, I also thought ‘This chick is not just keen on fishing; she’s got some staying power too’.

But all is glitz and glam and endless optimism in the digital world where everything seems possible and our minds fill in the blanks with more of what we want to see. After months of living in this cyberspace bubble of trout fishing romance we felt ready for a real-life encounter. ‘We should meet’ became our standing joke and a sign-off line. By early New Zealand winter, we started to hatch a plan.

She wanted to come for a week and I thought it was an awfully long way to travel here and back for just a few days of fishing. ‘Look, why don’t you come for at least a couple of weeks,’ I suggested. ‘I’ll guide you for the first few days because you’ll definitely need it, and from then on we can fish like friends, see if our trout dreams match, and how everything else falls into place.’ She said yes, but as we continued to talk our dreams and make plans it soon became apparent that even two weeks did not seem anywhere near enough.

‘Why don’t we just jump in at the deep end? Make it two months if you dare,’ I suggested, and to my greatest surprise Jennifer again said yes.

She booked her air ticket for late October. That winter at the Southern Lakes was one of the best ever, with an abundance of snow and sunny still weather, and so I was out ski touring every good day, sending Jennifer little movie clips of our ski runs, or chatting with her live from the mountain summits whenever cell reception allowed. Then the trout season started and I was back to River X, on my annual early-season pilgrimage, and every day I drove out of the valley and into reception so we could chat and reconnect.

‘Maybe we should send the Apple people some champagne or single malt with a thank-you note,’ we joked, ‘as without them this transcontinental trout romance could never be possible.’

After so many hours and terabytes of data it felt as if we had known each other forever and now, like kids before Christmas we were counting days: 14 . . . 10 . . . 5 . . . 3 . . .

But with growing excitement also came matching anxiety. Could we really do this? Could we truly live the trout bohemia dream of doing what we love with someone we love, finding a kind of trout soulmate in each other? And, could we face the disappointments of failure should our visions and dreams come crashing down?

What if this whole crazy plan did not work out? On the other hand, what if it did?

We were about to unplug from the digital reality, meet in real life for the first time, and find out.