My story about Mayflies in New Zealand Geographic is now out in bookshops and online

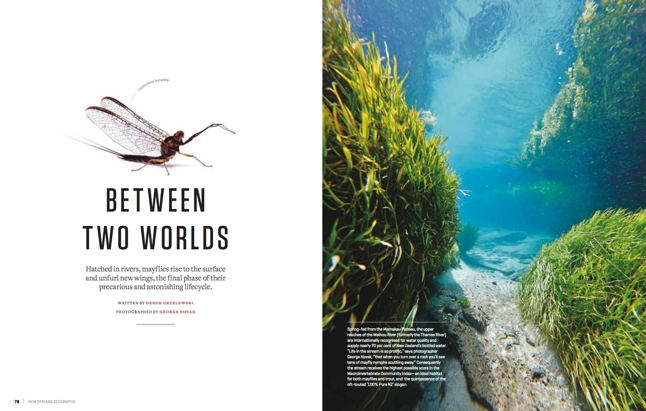

Hatched in rivers, mayflies rise to the surface and unfurl new wings, the final phase of their precarious and astonishing lifecycle.

At dusk, on the upper Waiau River under the swingbridge entrance to the Kepler Track, the mayflies were hatching. Each insect rose from a dimple on the water’s surface, then took a hyperbolic flight path, vanishing into the glowing Southland sky.

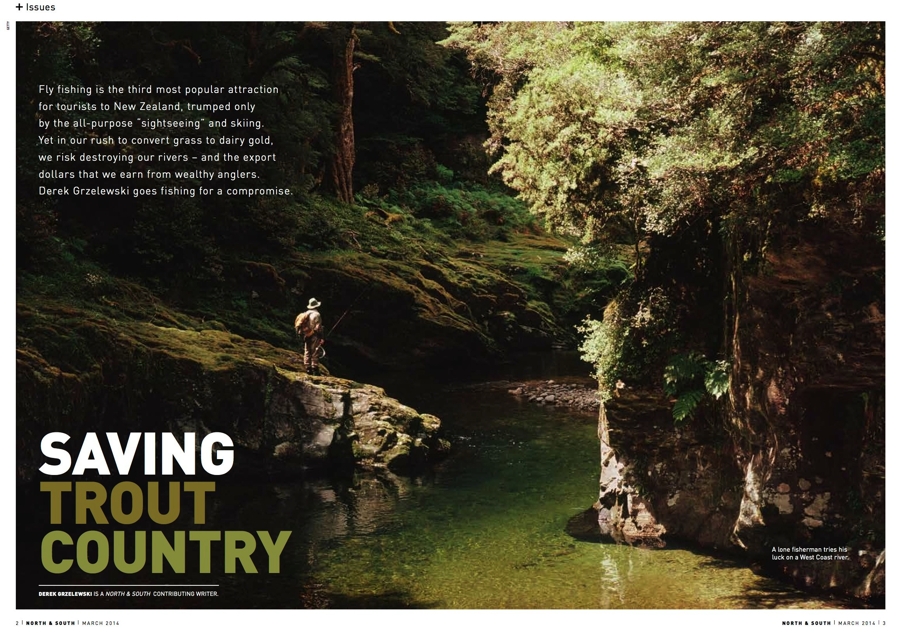

The mass emergence of mayflies attracts trout, which I had come here to fly-fish, but such was the explosive beauty of the spectacle before me, I put my rod away and just watched.

Mayflies spend almost all of their lives underwater among rocks on a streambed—usually a year, sometimes two in the case of the largest species. Then, when conditions are right, they ascend to the surface to hatch. There, they struggle through the viscous membrane that separates the two worlds and climb out of their nymphal shucks—think of a whitewater kayaker, adrift in a current, pulling herself out of a tight cockpit. Then they fly off, keeping their bodies vertical in flight, tails trailing like long legs, giving an overall impression of dainty ballerinas carried on gossamer wings.

Once in the air, they live only a day or two, to mate and procreate, to die and to fall back into the water. This phenomenon, and a misunderstanding of their complete life cycle, has given rise to their Latin name Ephemera—living for a day—to describe the fleeting nature of their existence.

Though trout hunt mayfly nymphs among the river gravels all year round, they are especially attuned to the calendar of the mayfly hatching. Ascending insects, briefly trapped in the surface film, are at their most vulnerable—away from the safety and shelter of riverbed crevices, caught out in the open and silhouetted against the sky. No surprise then that, as I watched, the weaving currents of the Waiau were roiling with feeding trout, the fish slashing and punching from beneath the surface, their jaws snapping like so many pairs of wet hands clapping shut.

But the mayflies’ strength is in their numbers and the brevity of their emergence. Some of the hatches in the United States have been so huge and dense, they registered on radar systems at local air traffic control. One species, Hexagenia limbata, erupts from the waters of the Mississippi in hatches totalling some 18 trillion insects—more than 3000 times the number of people on Earth. The newly emerged mayflies are attracted to lights in riverside towns and descend on them like a blizzard. Local authorities use snow-clearing vehicles to sweep up in the aftermath.

Above the Waiau, thousands of fluttering insects streamed skywards until night fell and the spectacle ended as if by the flick of a switch.

The trout were gone just as quickly and I turned on my headtorch, climbed up the steep rainforest bank and headed back to my camper, pausing for one last look at the river from the swingbridge. Only now I realised that, faced with this extravaganza of mayflies and trout, I had completely forgotten about fishing. This, it later turned out, was not an uncommon reaction, as many careers in entomology began with a fly rod. “You start by fly fishing for trout but after a while you stop bringing your rod,” one mayfly researcher told me. “The invertebrates are a lot more interesting.

all photography by George Novak