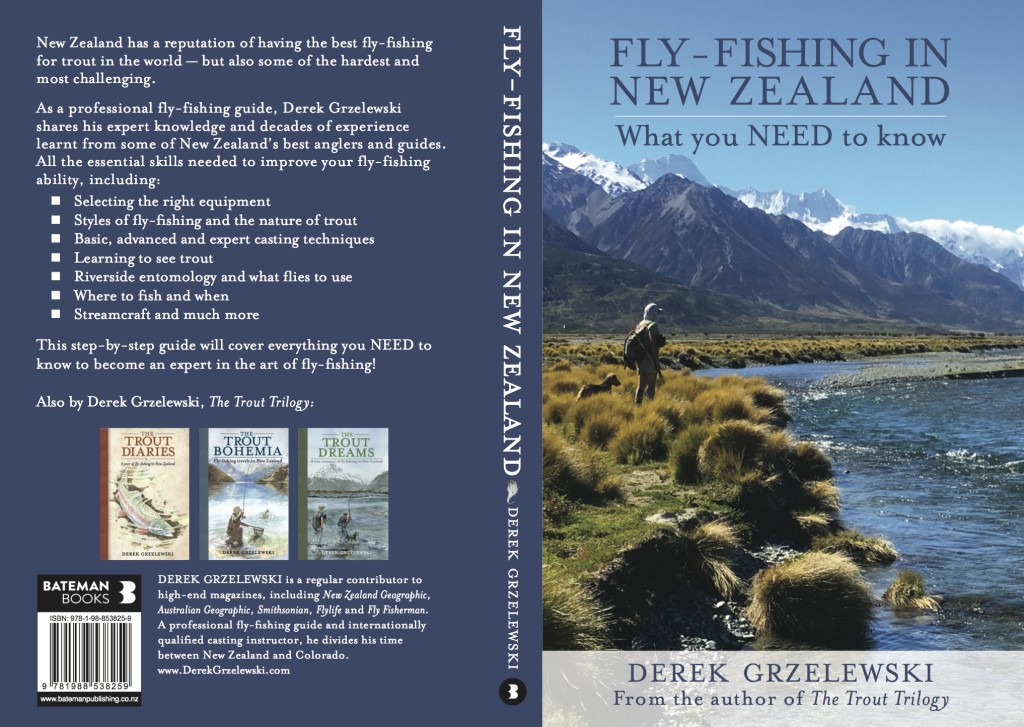

New book from Derek Grzelewski, the author of The Trout Trilogy, to be published October 2020

Free first chapter Pre-order the book here

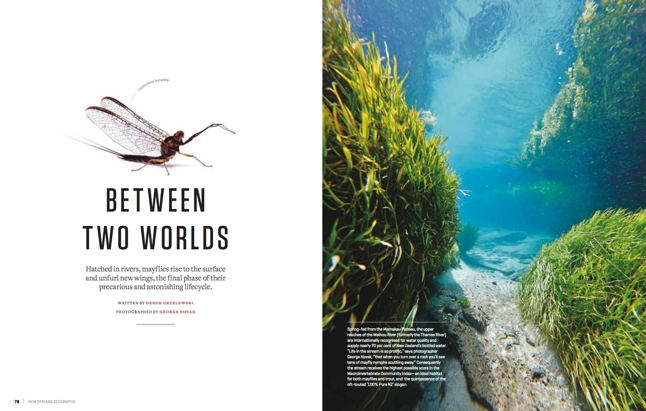

THE TROUT WERE RISING ALL AROUND US, as far as we could see, but we weren’t hooking any. I say ‘we’ out of politeness and empathy because I wasn’t actually fishing. I was chaperoning two gentlemen who had engaged me as their guide and described themselves as ‘intermediate’ anglers, and we happened upon an epic mayfly hatch, one of the best I’d ever seen.

Both men spend several thousand dollars to be here — airfares, lodging, guide’s fees and more — yet instead of having the time of their lives they were in the pits of misery. Hope and anticipation turned into despair and defeat with every attempted cast. Their fly lines slurped off the water and slapped down in loose or tangled heaps, flies hit parts of human anatomy, the air was thick with frustration and expletives. So many trout feeding in a frenzy, each the object of an aching desire, so close and yet so out of reach.

From what I could see, the rising trout — dimpling the water with a metronomic rhythm — were never in any real danger of being caught. Not one of them saw a single decently presented artificial fly all afternoon. And so ‘we’ blanked that day. What could have been a lifetime memory was perceived as an embarrassment to be forgotten and drowned in whisky.

Compare that with another day on the same river, with a different angler and almost no trout activity. We walked and waded, across and back, and the only active trout we could find were in heavy cover, on the edges of trailing willows, often right under the branches. None of this seemed to faze Mike. Despite having only a handful of opportunities that day, he didn’t waste any. Each of his presentations, though often not perfect, was an honest ‘as good as you can make it’ effort and the trout responded with likewise honesty.

‘You need to side cast under that branch, Mikey,’ I’d say, or ‘Try a reach mend to the left on this one.’

And Mike would say: ‘Got it!’ And he did — the cast, the mend and the fish. We ended up with several good trout on what could have easily been a blank day. It was all a pleasure to watch, and a joy to be a part of.

Can you relate to these scenarios? Which of the anglers would you rather be?

I have now fly fished for over 30 years and guided for half of it. As fly fishing for trout goes, I can honestly tell you I’ve seen it all: the best that borders on sublime art and poetry in motion and causes you to involuntarily gasp in wonder, the worst that makes you want to sell your gear and give it up altogether, and most things in between. Fishing with friends, mentors, guides and clients, I have seen the patterns of success and patterns of failure and, having an enquiring mind and passion for learning, I’ve come to discern the difference.

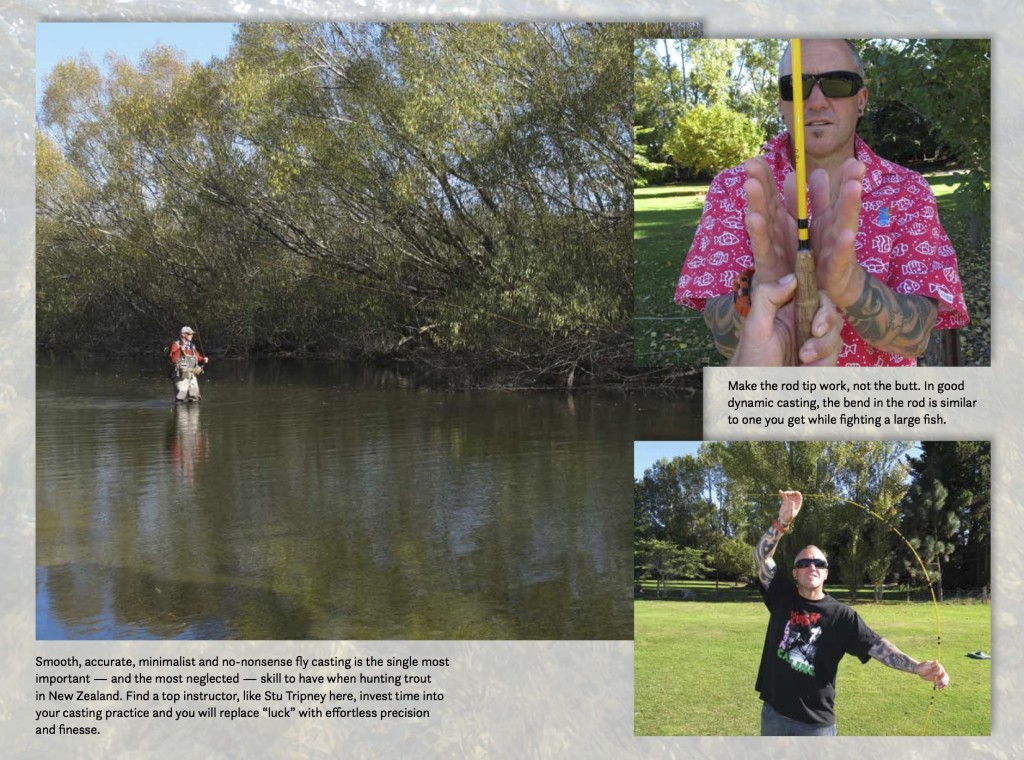

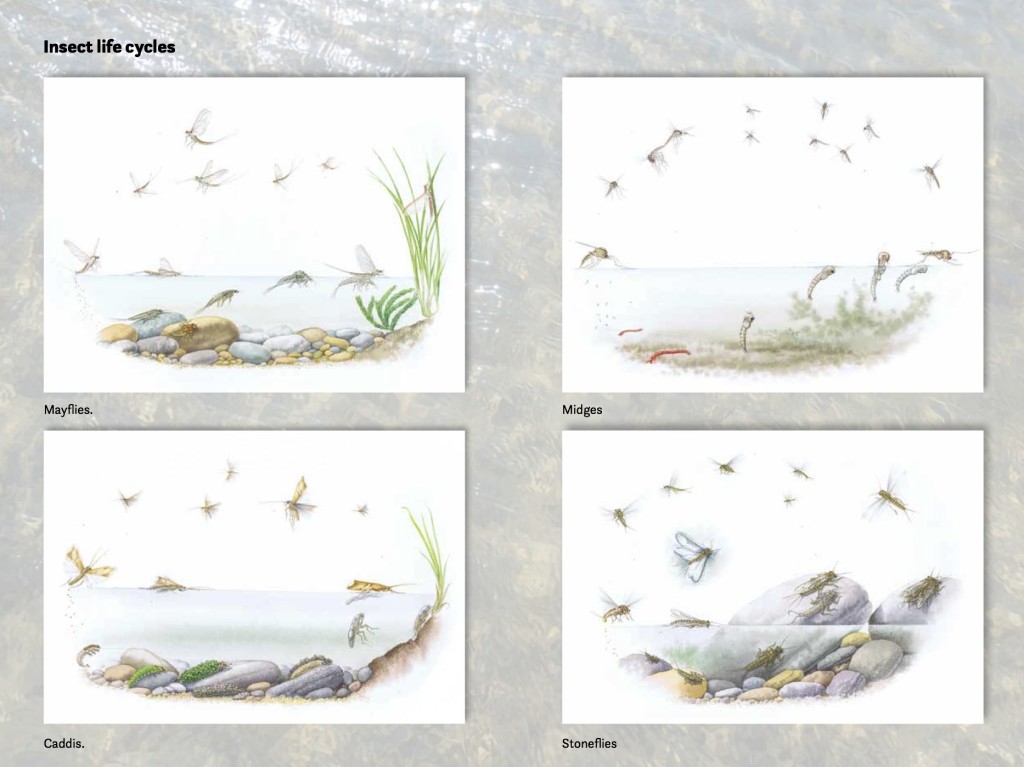

Fly fishing is not difficult, but it is complex and there are plenty of ‘experts’ out there who insist on making it even more so, perhaps because this makes them feel more knowledgeable and important. Hence you get lectures on leader construction and how to perform a bucket mend, a detailed life cycle of Ameletopsis perscitus and the 1000-plus fly patterns not to leave home without. All of this is interesting, but also — for an enthusiast with limited time — it can prove overwhelmingly complex, an overload of information that is daunting to absorb and process, much less to apply, which can make you feel like you never know enough.

The good news is that if, as the saying goes, God (or the devil) is in the details, it is not in all the details. And how are you to know what’s key and what’s optional? I wrote this book to provide an answer to that question.

The trouble with learning to fly fish, and progressing further along the angling journey, is that most of the learning happens in a random and haphazard way. When you learn to ski, for example, you follow a structured progression: wedge, parallel, short turns, off-piste, backcountry, heli-skiing. As a never-ever on skis, you wouldn’t dare to go heli-skiing, yet in fly fishing such short-cut scenarios are common, and the results are just as predictable.

Most often, anglers — though eager to learn — end up collecting hot and secret tips from the ‘experts’ and friends but do not have a foundation or structure to add them to. These titbits of knowledge may be interesting, but they are not necessarily useful or useable when out of context. It’s like having a lot of bright and dazzling Christmas decorations and no tree to put them on.

You want to grow your tree of fly-fishing knowledge so it is strong, tall and straight, with solid roots and clean branches that spread in directions of your fancy, and then you can decorate it all with anything you like. In Fly Fishing in New Zealand, What You NEED to Know I’ll show you how to do just that.

Of course, it’d be hard to find a more opinionated community than that of fly fishers, where for every opinion and perspective you may have one diametrically opposing — and just as valid. My intention here is not to stir up another controversy or to attract the wrath of experts but to go beyond any and all opinions, perspectives and preferences, to the level of universal fly-fishing truths from which all anglers, no matter at what level, can benefit.

I’m not proposing to make fly fishing easy or simple for you. It is not, and you wouldn’t want it to be anyway. But I promise you that, if you follow, apply and integrate the progression of skills and concepts in this book, you will be in the top few per cent of all anglers.

Why? Because, sadly, a great majority of them won’t put in the time and effort required, and instead they continue to hope that the next gadget, new rod or magic fly will get them to connect with the dream fish, not realising that a cleaner and more direct way to fly-fishing competence is through investment in oneself.

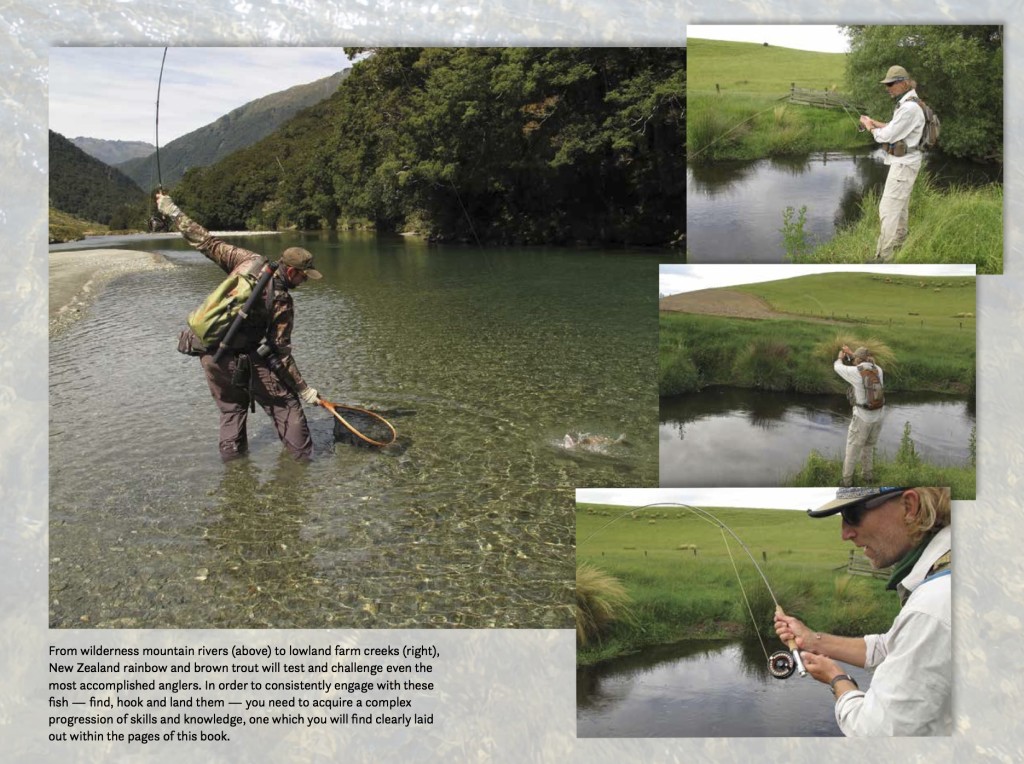

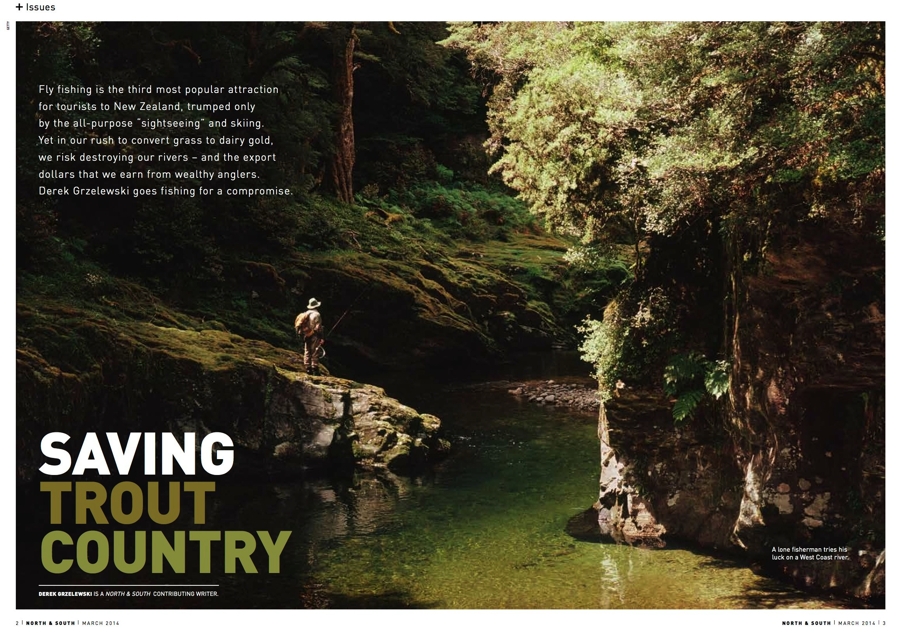

The information presented in this book has been distilled from the skills and experiences of some of New Zealand’s best anglers and guides whom I have had the privilege to fish and spend time with over the past three decades. New Zealand has the reputation of having the best fly fishing for trout in the world but also — as most visitors will attest — some of the hardest and most challenging. After fly fishing in New Zealand, anywhere else may seem easy. I don’t mean this in any derogatory way. It’s a simple fact: in New Zealand, unless you refine your skills to the best they can be, you may get lucky every now and then but, overall, you’ll end up fishing a lot but not necessarily catching very much.

Though the skills and concepts presented in this book are based on fly fishing for trout, the underlying principles and fundamentals are universal and can be applied to other types of water and fish species. You’ll just have to tweak a few details, but you will know which ones. You will know what questions to ask and the local guides and experts will see and recognise it. You’ll put smiles on their faces instead of seeing them slap their foreheads in despair. Likely they may tell you, or at least silently mean it, that fishing with you on their waters is a pleasure to watch, and a joy to be a part of.

Does this book contain all there is to know about fly fishing? Of course not. Fly fishing is an open-ended and evolving concept. There is always more to know and to learn, and that’s one of the enduring attractions of our sport. But, at whatever level you are, on the following pages, you’ll find what you absolutely NEED to know, the road map to guide you through the complexity of fly fishing, a coordinate by coordinate route to becoming a top angler. Follow it and you won’t get lost. You may still take and enjoy any side trips that present themselves, but your homing sense on what’s core and what’s optional will become as strong as that of a returning salmonid. This journey through the world of fly fishing has certainly been one of the greatest adventures of my life and I hope, with the help of this book, it can be that for you too.

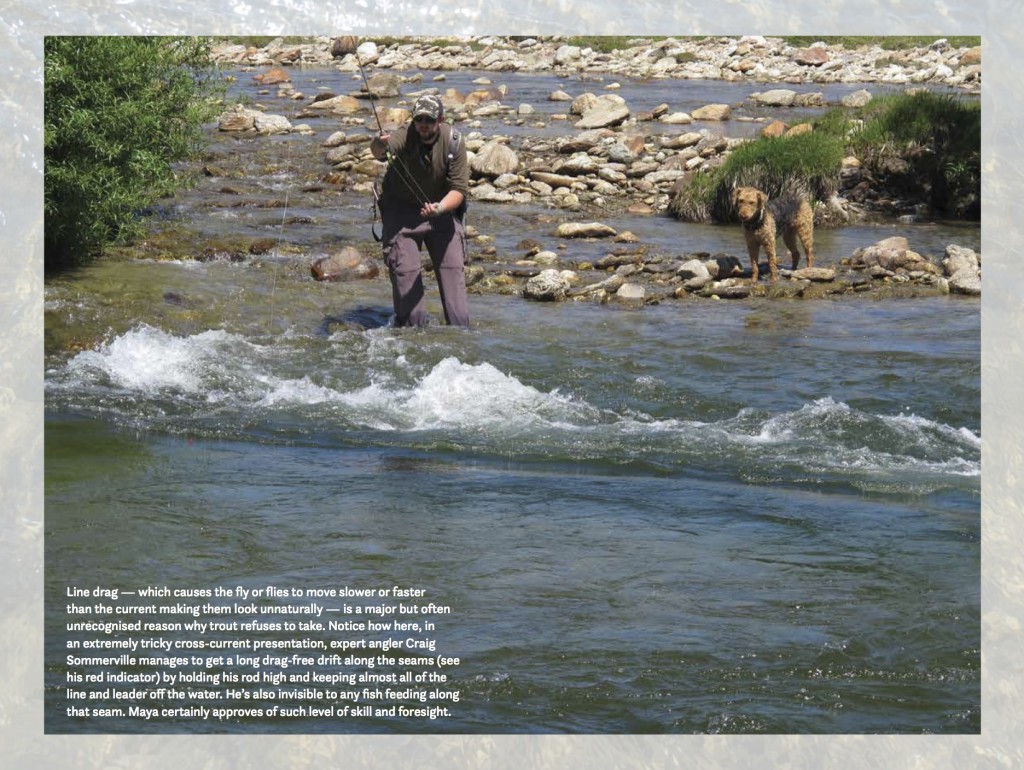

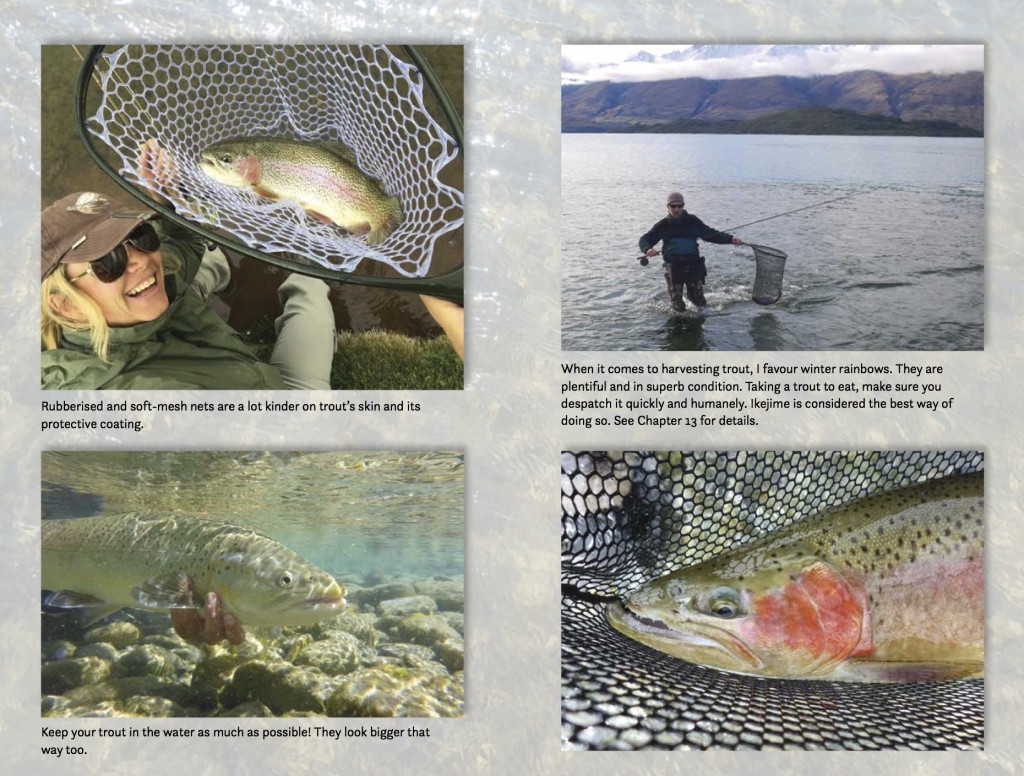

Fly fishing is not difficult, but it is complex. There are no quick returns and instant gratifications, no short cuts worth taking. You need to know what the fish feed on, where and when and at what depth, what is the size and colour of the ‘food’, how to best present it realistically and without spooking the fish, whether or not you need to move it and if so how, and, finally, what to do and not to do if or when the fish actually takes the fly. Which, as you can already see, is a lot to figure out!

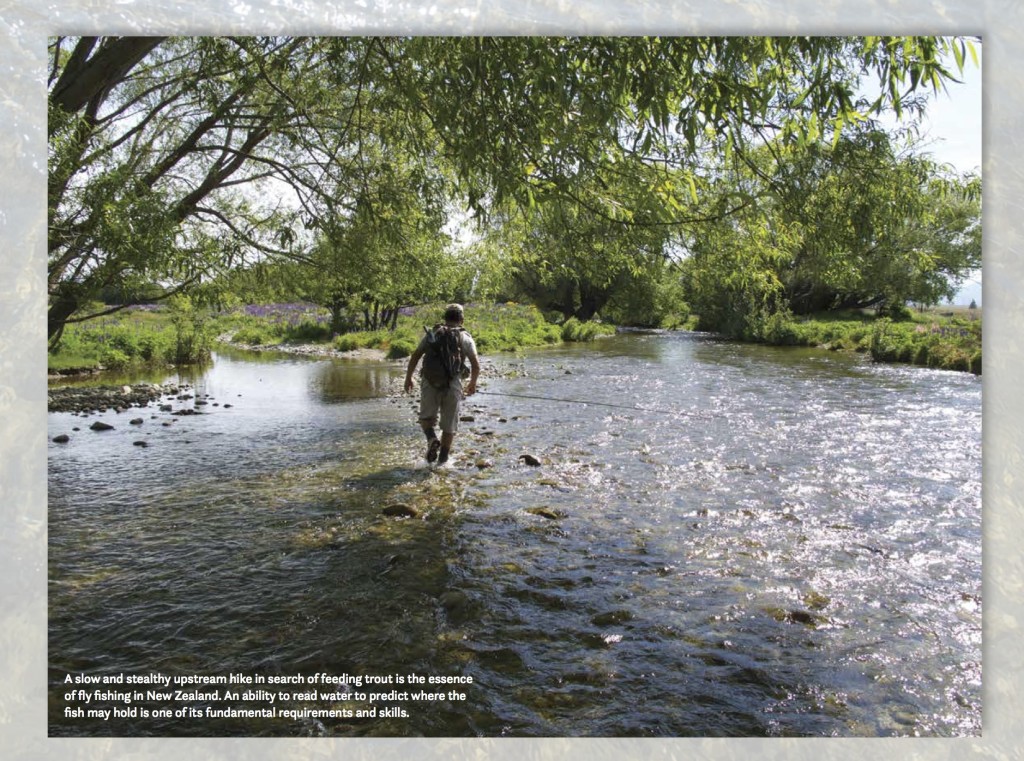

This is why, and before we get into any techniques and strategies, tricks and tips and secret flies, you need to realise that the greatest skill in all of fly fishing is your ability to observe what’s going on in and above the water, to draw conclusions from what you see and adapt your approach accordingly. Often anglers come to their chosen fishing water with a preconceived idea of what they will find there. Sometimes their gear and flies are already pre-rigged; perhaps it was something that worked in the past so they hope it will work again. It might, but observation is a more powerful and active approach than hope. You may have heard the famous philosophical credo that ‘No man ever steps in the same river twice, for it’s not the same river and he’s not the same man.’ Well, it is as true in life as it is in fly-fishing.

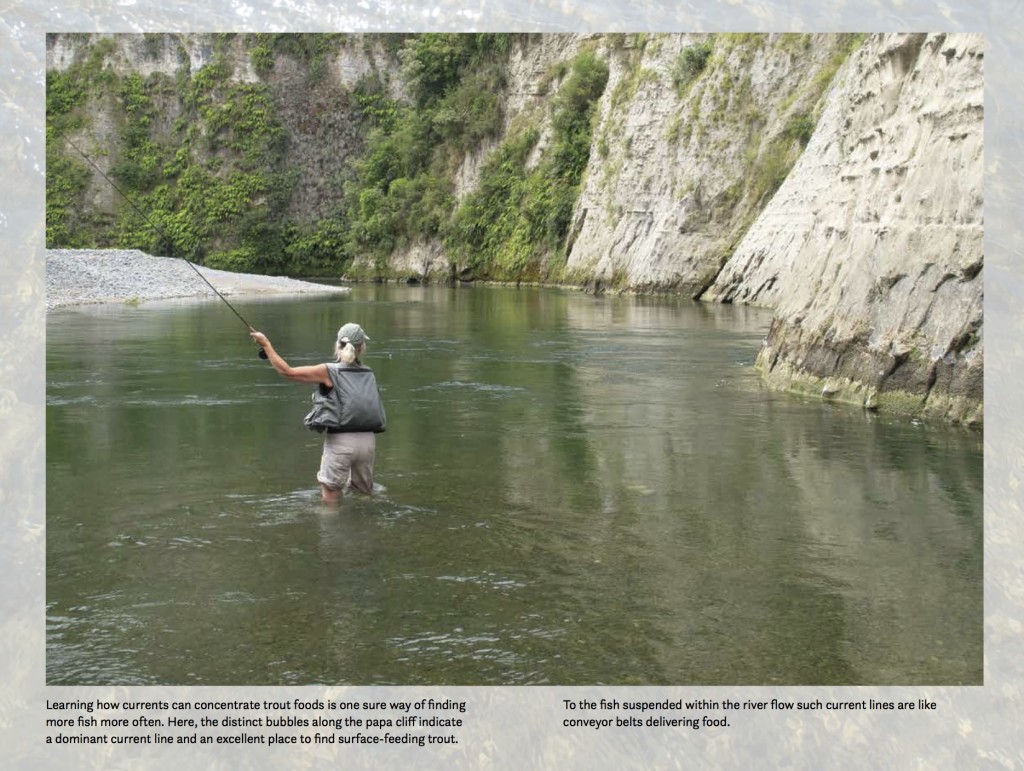

This is why you always want to approach your fishing water as if for the first time. Go slow: why rush a good thing? Let the hunter’s genes that might have gone dormant or numb due to our crazy fast-paced lifestyles reactivate within you in response to the natural stimuli of the river world. Slow down to the pace of the water, and as you do, it will reveal to you its secrets: fish and then some. You see, on a river, almost all the information you need to catch fish is all around you. You just need to tune into it and learn to interpret what you perceive.

This may sound a bit esoteric at this point, but as you gain knowledge and experience the disparate pieces of the complex puzzle that is fly fishing will join for you one by one to reveal a picture of exquisite beauty and depth. That picture will of course change with the seasons and places, but it will no longer intimidate you with its complexity. Rather, it will invite and entice you to explore it further and deeper, to move around it with confidence, at the same time reminding you frequently that, for all we know and want to know, fly fishing will remain inherently unpredictable. It will elate you, and frustrate the hell out of you, it’ll send you to study books on insect life cycles and sign up for the fly-casting clinic again, and then go back to the river for more surprises. Which, I guess, is why we go fly fishing in the first place.