An excerpt from The Trout Diaries, A year of Fly Fishing in New Zealand

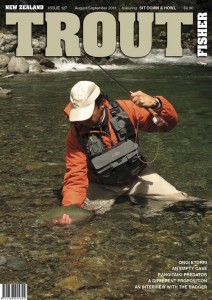

In the Taupo backcountry, in the illustrious company of the CDC guru Marc Petitjean and trout scientist Michel Dedual, Derek Grzelewski fights trophy rainbows and other demons.

Have you ever been on a fishing trip, a long-planned and much anticipated, where nothing goes right for you? You arse up just stepping out of the helicopter and give yourself a good one on the shin. You promptly trump this with another act, stepping on the loose end of a vine with one foot, with the other tripping over the noose you’ve thus created. You want to break the fall with your hands but they are full of camping gear and heavy supermarket bags, and your backpack, well, it’s just big and inert enough to prevent a recovery. Your companions help you up and give you puzzled looks. And you too wonder: what’s going on? Is it just me or some nasty local taniwha who clearly does not want me here?

Have you ever been on a fishing trip, a long-planned and much anticipated, where nothing goes right for you? You arse up just stepping out of the helicopter and give yourself a good one on the shin. You promptly trump this with another act, stepping on the loose end of a vine with one foot, with the other tripping over the noose you’ve thus created. You want to break the fall with your hands but they are full of camping gear and heavy supermarket bags, and your backpack, well, it’s just big and inert enough to prevent a recovery. Your companions help you up and give you puzzled looks. And you too wonder: what’s going on? Is it just me or some nasty local taniwha who clearly does not want me here?

Maybe it’s both because things get even worse. On the river, you tangle up, spook every trout you see, hook yourself with your own fly, the one you did not yet de-barb. By contrast, your companions are having time of their lives. That first night in the headwaters of the Rangitikei, after we set up a camp in the forest clearing, Michel trotted off for an evening hunt and only minutes up the creek bagged a decent-size sika deer. He brought it down, dressed and hung it from a tree, then, going down to the creek to wash his hands, he spotted a fish rising in the camp pool. He ran back for his rod and hooked the six-pound trout first cast. A pool below I was with Marc, watching him fight an equally magnificent rainbow. When the night fell all I had to show for was a limp, a grazed elbow, and an increasingly foul mood.

But then we were back in the camp, the fire, wine and good food working their wizardry. I stared into the flames, sipping another glass of red and thought: “hey, anyone can have a false start, a bad day, and mine was just about over.” Earlier, I even spilled some wine on the ground, a peace offering to the taniwha, if there was one. I certainly did not want to fight it for another day.

The upper Rangitikei, clear like spring water, snakes a contorted passage through the volcanic hills of the Kaimanawa Forest Park, east of the Tongariro. The fishing here is hard and honest, every fish a major victory, and that’s providing you are at your best, sharp and assertive. Tomorrow, I promised myself, was a tabula rasa I should fill with perfect casts and beautiful fish. No pratfalls and blunders. I fell asleep with the visions of rainbows racing each other for those beautiful CDC dries Marc was tying.

I have to tell you about Marc. This was, after all, his trip. He had travelled halfway around the world for these five days on the Rangitikei, and Michel especially did all he could to make those days into a memorable outing. Once on the river Marc needed no help at all. As Pasteur said “good fortune favours the prepared mind” and Marc Petitjean was more prepared than most. “If you define the problem, the solution is often obvious,” he told me that first night, apropos nothing. “People often get pissed off with themselves and they don’t know why. They never take time to precisely identify what bugs them. If they did, the remedy would be self-evident.”

Wise words but lost on me at the time.

The next morning I scooped out a large mayfly nymph out of the river with my stainless steel mug. The aquatic insect life in the Rangitikei is so prolific, every time you dip a pot, a plate or even cupped hands in the water you capture one of the little beasts. No wonder the trout grow so large here.

I took the mug back to the camp and Marc examined the critter closely, then whipped up a dozen or so imitations in three sizes. He also tied a handful of CDC dries, his generic mayfly pattern with an added white parachute post for high visibility. The post was made from the tail hair of Michel’s deer. Though we had brought with us enough flies to start a riverside tackle shop, in the end these two patterns were the only ones we would use. The Rangitikei fish either took them within the first couple of casts or they would not take anything at all.

If you have not heard of him before, Marc Petitjean is the man responsible for the modern-day global renaissance of the CDC flies, both dries and nymphs. When he is tying, his hands are a blur, a testimony to some 25,000 flies he has produced each year during the past decade, using up over a quarter tonne of Cul de Canard plumes.

Marc had also brought the Swiss-army-knife kind of technology and engineering into the world and the bench of fly anglers. His vise, vest and fly tying tools, after you’ve seen them for the first time, instantly fall into a must-have category. His bobbin holders, for example, as easy to thread as striking a match, are in such demand he simply cannot produce enough of them. His fishing too turned out to be as elegant as his gear.

In the morning we started up the river. With good sunlight and the background of mossy cliffs the fish were easy to see but, for a while, catching one seemed beyond the abilities of any of us. Browns, you could not touch. Even lifting a rod to initiate a cast was enough to send them off at speed. One in three or four rainbows offered a fair chance and these odds did not take into account human errors or gaucherie.

I had only two opportunities that day. On one I hung up a cast and by the time I untangled the fish was gone. On the other, an unexpected gust of downstream wind dumped my 16-foot leader on top of the fish. It was like throwing a rock at it: one moment it was there, the next it was gone, dematerialised. Was this mongrel of a taniwha still following me? I gritted my teeth and took solace in watching the faultless travails of my companions. Despite the odds, Marc has eked out two beautiful fish, and Michel had another one. For a day on Rangitikei it was really good going, and all this happened even before the godsend of the evening rise.

With the onset of the nightly mayfly hatch, the fish so difficult during the day suddenly become bolder and more visible, even a little careless. Even if you had not touched a thing all day you could relax in confidence that the twilight half an hour should produce enough opportunities to be converted into fish with even a modicum of skill. Unless, of course, you have your demons for company, and make a foolish gamble like I did.

On the classic South Island dry-fly rivers I fish regularly, if there’s going to be an evening rise, you can fairly assume it’ll happen in the slower, smoother bottom third of a pool. So as we divided a long cliff pool into thirds I chose that very section then, all gear ready and double-checked, set out to wait.

And wouldn’t you know it, the Rangitikei trout do not rise in the tail of the pool. They rise at the top end, just below the whitewater of the riffle. In the dimming twilight some fifty metres above I heard a heavy splash, then Michel’s laughter echoed down the cliff bank.

“Hah! She is a beauty, this one!”

It wasn’t long before Marc had a fish too. In the space of intense thirty minutes they landed half a dozen fine rainbows between them while absolutely nothing happened at my end.

It was almost dark when, finally, a fish rose some ten metres in front of me. Instantly I had the CDC mayfly in the trout’s window of vision. Another rise and moment later, a violent tug against my line. Then, where the rise had been, a hefty fish leaped, flashing silver against the gloom of the forested cliffs. It bounced off the surface twice, then buried deep into the inky water, tearing off fathoms of line.

Now I had it on the reel, under control. My throat was lumpy and dry. Man, finally. I had a fish on. I was back from the lala-land of botchery and blunder. The reel sang, these were the sweetest moments. Then, would you believe it – Twang! – the fish broke me off. “The world’s strongest fluorocarbon” snapped like the tying thread pulled too tight. I wanted to sit down on the bank and howl.

The next morning we packed for an overnight bivvy and headed back up the river. Half-heartedly I plodded behind the others, deriving what pleasure I could from watching them fish. I hooked a nice fish early in the morning – first cast, good take, no problems. But then the little steel Mikro-ring which connected my leader to the fluorocarbon tippet, well, it …. Yeah, I wouldn’t believe that either.

Still, there was another sure-bet evening rise. This time I’d have a whole pool to myself. I claimed the one near the camp – long, deep, well-structured, untouched for days.

“Good choice,” Michel approved. “Every evening I spent here we’ve always caught really nice fish.” Then they both went a couple of pool upstream and I was left alone.

I built a small fire away from the river, and much later, after it got completely dark, I watched the lights of my friends’ two head torches groping their way back down and across the river, toward my fire.

“How did it go?” I asked when they arrived.

“Fabuleux!” Marc exulted. “We had a double.”

“A trophy?”

“No, a double hook-up,” he corrected. “We got others, too, four or five altogether. And you?”

Well, what could I say? All evening not a single fish rose in Michel’s never-fail pool. The most troubling thing was that, by now, I wasn’t even surprised.

The night was rough. It rained, softly at first, then harder, and our little tarp leaked, and sagged and flapped in the wind. Despite all that I slept well, totally at peace with myself. The previous evening by the fire, I had a little tête-à-tête with the demon.

“Listen you son of a bitch,” I told him. “Enough is enough. I can take a day of this, two days max, but not the whole trip. Why don’t you stop being such a sadist and let a guy catch himself a fish or two.”

Word by word, I worked myself into quite a soliloquy, unloading my sorrows and grievances, after a time at no one in particular. It was like a psychotherapy session, minus the shrink. The North American Indians call this sort of thing a sweat lodge, only that they really sweat their stuff out in an improvised steam sauna.

I don’t know if this in any way defined my problems, made the solution obvious and self-evident but I woke up feeling fresh and free. The rain had discoloured the river but not too much. We could still spot the fish but they could no longer see the ruse of drifting artificials. Marc and Michel quickly had a fish each, then there was a long barren stretch without much holding water.

Partway through it we hesitated whether to go on. It was nearly midday and we had a long descent ahead of us. The vis was poor at times. Gusts of wind played havoc with our casts spooking fish and the sky darkened again promising more rain. Both Marc and Michel were happy to head back. They already had an impressive tally of fish, and me, well, by now I’d sort of given up on ever catching one here.

Still, we lingered, teetering in indecision. Was it really it then? The end of the trip? Then someone said “Hell, why not, let’s go up another couple more pools.” This was a turning point for me, clear and obvious though only with the benefit of hindsight.

We were coming to the first large pool in a while when from up ahead Michel called:

“Dereque! Here’s one for you. He’s taking everything that’s passing by.”

Great, I thought. How’s that for show of confidence in my skills. But maybe I needed a fish like that, a real dumbo, one that would take a cigarette butt if you floated it past without drag.

I got into position, took a deep steadying breath and cast. There was not the slightest hesitation in the trout’s swaying dance. It took my nymph, then another natural, then another still, then, suddenly feeling the tension of my line, erupted out of the water. It jumped again, and again, flapping all the way up, like a salmon trying to leap over an obstacle. Wonder of wonders, nothing went wrong. The knots held, the hook did not come out, there were no tangles. I beached him in a little bay of sand, a solid Rangitikei rainbow, all spotted chrome and crimson fire. Unhooked, he was gone in a flash and I was left breathing hard, the hands still trembling.

Meanwhile, Michel was into another fish and was briskly leading it downstream, with Marc following, taking pictures. I wanted to be alone, to relish the moment and my turnaround, and I went upstream, no more than a dozen paces. There I saw it, at the bottom between two boulders, a long dark smudge, soft and swaying with exquisite fluidity.

I felt strangely calm, absolved from my dog days of bad luck and gaucherie, with a mind that was pure and unafraid of screwing up. I put a single cast ahead of the boulders. As if in slow motion, I watched the fish veer to my side and take. Next thing I was running downstream, hot-footing over the stones, taking up the slack as I ran. My line wrapped around the reel handle but I caught it just in time, and I had the fish on the reel, sword-fighting it left and right against its furious runs.

Then I was kneeling over it in the same sandy bay and I felt my companions peering over my shoulders.

“Tres bien fait!,” Marc enthused. “Fabuleux!”

“You ever caught a fish that big?” Michel asked, a lopsided grin stretching his moustache.

“Well, sure …” I started but then I took another look at my trout. He wasn’t particularly long, but he was deep and broad, with the brilliant metallic skin that seemed too small for him.

“How heavy you think he is?” I asked.

“A ten,” Michel said.

“Naw! You sure?” I was incredulous.

“Ah, easy.”

We had all years ago dispensed with carrying the scales so there was no way of verifying this.

“I think you can trust his judgement,” Marc said later and I had to agree. In his work as a trout scientist for the Taupo fishery Michel gets to handle and weigh hell of a lot of trout.

But I shall never know for sure if the fish was a double and maybe it’s better that way. It was certainly the biggest fish of the trip.

The last morning I walked with Marc up a tributary which entered the main river not far from our camp. We did not see a fish but casting blind into the most likely spot Marc landed one more fabuleux rainbow. At this we took down our rods. The helicopter would be coming soon, it was time to go.

Before we left, we each took a handful of creek water and touched the hands together like goblets, a toast to the Rangitikei. I had spilled some of mine on to the ground too, another offering, this time not to appease but to thank. The demons, whether local or personal, were as playful as they were generous. Their pranks and antics had really made my trip.