THE TROUT BOHEMIA

Fly Fishing Travels in New Zealand,

by Derek Grzelewski

Published by David Bateman (NZ) and Stackpole Books (USA) 2013

‘Once upon the time a prince met a beautiful princess.

“Will you marry me?” the prince asked.

The princess said, “No.”

And the prince lived happily ever after. And he fished, and skied, and hunted, and went on long safaris, and he drank expensive whiskies by the campfire, and there was no one there to tell him he played too much, and that it was costing a fortune . . . ’ Anonymous

‘For us, New Zealand is a dream come true, the trout Bohemia.’ Jetske Darbeaud

‘A seeker of silences am I.’ Khalil Gibran, The Prophet

‘Is that it then? Is this how it all ends?’ she asked, and I did not have the courage to meet her eyes.

For the past half an hour, with a heavy heart, I’d been telling Ella how this togetherness of ours was not working for me any more. How, after the autobahn of a long honeymoon, our road was getting more and more rocky and potholed, and how I was increasingly unsure I wanted to travel it. I’d been telling her how I grew tired of conflicts and dramas, how it seemed I was forever putting out fires and whenever one was out, another would flare up elsewhere until, in the end, I’d given up and thought, ‘Well, just let them burn.’

All the time I talked, she held me with a steady gaze and listened silently, two rivulets of tears running down her beautiful sun- browned face. Now that at last she had spoken, asking the question loaded with so much finality, I could not bring myself to answer it.

Truth was I didn’t know. Despite our best intentions and contrary to earlier promises and reassurances, we had lost our way. Maybe we just went into it all too hard and fast, two stubborn individuals burning with many passions but unable or unwilling to compromise. Or perhaps we were just not compatible. I really didn’t know any more.

I could feel Ella’s eyes probing me for answers, but the words failed me. I got up and gave her a peck on the cheek, tasting the saltiness of tears, then headed for the door. With my hand on the doorknob I turned to her one last time. She was still there on the couch, paralysed in stillness, her usually tall and proud ballerina’s body crumpled as if the bones were suddenly gone from it and there was nothing to hold it up any more.

‘I need to go away for a while,’ I said. ‘Let’s put some time and space into this. Maybe then we can piece it all back together.’ For a couple of beats I waited for a word from her but, as none came, I stepped out through the door and slid it shut behind me. The metal frame gliding on rollers sounded like the fall of a guillotine. Whoosh! Maybe it was how it all ended.

‘The solution to any problem — work, love, money, whatever — is to go fishing, and the worse the problem, the longer the trip should be.’ John Gierach

It was early October, in New Zealand the beginning of trout season. My 4WD camper was parked in the driveway, ready to go, and Maya, my Airedale terrier, was sitting in the driver’s seat, waiting. As I was getting in, she gave me a double lick of greeting while her tail walloped the seat cover, raising puffs of sand. Then she moved over to the passenger side. It was her seat again, now that there were only two of us in the camper. I backed out on to the road and, once on the main highway, felt the Land Cruiser pick up its momentum.

I took a deep breath and it came out as a seismic sigh, and Maya’s tail walloped three times like the clap of applause. It was time to cheer up, she was implying. As so many times in the past, and they were always good times, we were again ‘Gone Fishing’ together. Might be some time and out of range. Incommunicado. Address unknown. We were going to the best place we knew: to the peace, solitude and the silences of the rivers.

SIGNED COPIES of THE TROUT BOHEMIA are available in my online bookshop here. Worldwide shipping.

Two hours later we were in Southland, heading further into the vast green plains through which so many good trout rivers meander. In spring, Southland can be a volatile place and this time it was no different. Apocalyptic hail storms bore down on us like giant waves from the Roaring Forties, pelting the camper canopy with hailstones the size of peas. The ice bounced off the road and crunched under the tyres. There were bands of brilliant sunshine in-between the storms, and full, double-arch rainbows, and this stark illumination made the farm hills glow with surreal green, so bright it seemed almost fluorescent. It was blinding like the surface of a glacier but lush and fresh and dotted with the confetti of shorn sheep and lambs prancing on newly found legs.

The forecast was good so I was not too concerned about the passing tempests. Here and there along the way, at Anglers’ Access signs and by numerous bridges, I saw fly-fishers’ cars parked, each staking a claim of privacy to an upstream beat, but the opening- day fever was tapering off and I was confident that, like every early season over the past decade, I’d have ‘my’ river largely to myself.

By now, the sense that by driving away I was stretching some invisible rubber cord which would either snap or pull me back to Ella was gone, replaced by the gravitational pull of the river which was growing stronger. I hadn’t been back here for nearly a year and the anticipation was delicious. Butterflies in the stomach. It felt like going to visit an old friend — solid and reliable, always welcoming and always there in times of need.

The river is not especially well known, nor is it a better fishery than any other waterway in Southland. But because of my experiences there — the rapid evolution of skills it had forced me into, the friendships and camaraderie I’d found there, the moments of magic so numerous and stacked so close together they overshadowed all other memories — it has always been a special place for me. Secret and sacred. The river of the heart.

Two years had passed since I completed The Trout Diaries and much had happened in the meantime. Firstly, like a doting teenager again, I had fallen in love just as when, this late in mid-life, I thought I was immune to such afflictions. Then there was the sad news from Grandpa Trout.

At the age of eighty-two, the itinerant Frenchman and my self- appointed fly-fishing mentor, decided he would not be coming to New Zealand any more. Although my river of the heart was also one of his most treasured places in the world, he reasoned that he had evaded old age and its associated infirmities long enough, and now they were catching up with him — strict diet, exercise regimen and happy river life notwithstanding. Nothing was wrong as such, but he had grown apprehensive about spending six months, much of it alone, in the backwoods of a country where he did not even speak the language.

He would still go to Quebec and the rivers of the Gaspé Peninsula for the Atlantic salmon season there, but it was unlikely we’d see him in New Zealand again, and for all those who had got to know him it was much sadder news than we dared to admit.

Grandpa bought a little apartment in France, not far from where he grew up, and he was back on his home river again, one where he learnt to fish as a boy. Some decades ago, the river’s entire ecosystem had been wiped out by a toxic spill from a

paper mill in its upper reaches, but the waterway was almost fully recovered, and large sea-run trout had entered it again, and they were cunning, intelligent fish, Grandpa assured me, adept at taunting the best of fishermen. They were impossible to catch, by the rest of us mere mortals anyway. In him, however, they might have just found their match. Perhaps all the fly-fishing he’s done so far — the past twenty years of averaging some 300 river-days a year — was only training for this highest of challenges.

The last time I saw him was the season past in Reefton, in the campground where he always rented a cabin. The inside was suitably Spartan, just as he liked it, and he had his cooking gear set out. He made us pommes frites for dinner, French fries comme il faut, the way itinerant fritiers of old used to make them, hawking their fares from a cart towed by a bicycle. They deep-fried the potatoes twice — slow and at low heat first to cook them right through, then cranking up the temperature to expel the oil from the chips, and to leave them crisp on the outside but light and soft like a sponge under the crust.

Over those, a bifteck and a bottle of red, which he drank religiously now only because his French doctor had prescribed it, we got lost in our usual river talk. About the virtues of some leaders and tippets over others. Flies that worked well that season and the sure-fire ones that disappointed, about the fish that we remembered because of how we caught them and others, even more memorable, because they would not be fooled. And never once did he mention that we were seeing each other for the last time. I bade him a bon voyage and said I was looking forward to fishing with him again next season, and he just smiled and stood there by the doors of his cabin as I drove away.

Since the year of the Diaries I hadn’t seen Henry Spencer either. I hadn’t heard from him and, considering the fragile state he was in back then, I feared the worst. Maybe his battle with cancer was not such a clean win after all, not as clean as he wanted me to believe, wanted himself to believe perhaps. I could not imagine him in relapse, bed-ridden, hooked up to chemo and IV fluids. It would have been like putting a wild trout in an aquarium, with an oxygenating pump and a timer feeder. Too cruel to contemplate.

Yet while all this and more went on, the trout rivers continued to flow, ever fresh and self-renewing. To me, they are the epitome of change, a reminder that everything everywhere is in a state of flux, and that holding on, whether to memories or a pleasing status quo, is a futile effort. Because life is like a river, forever on the move.

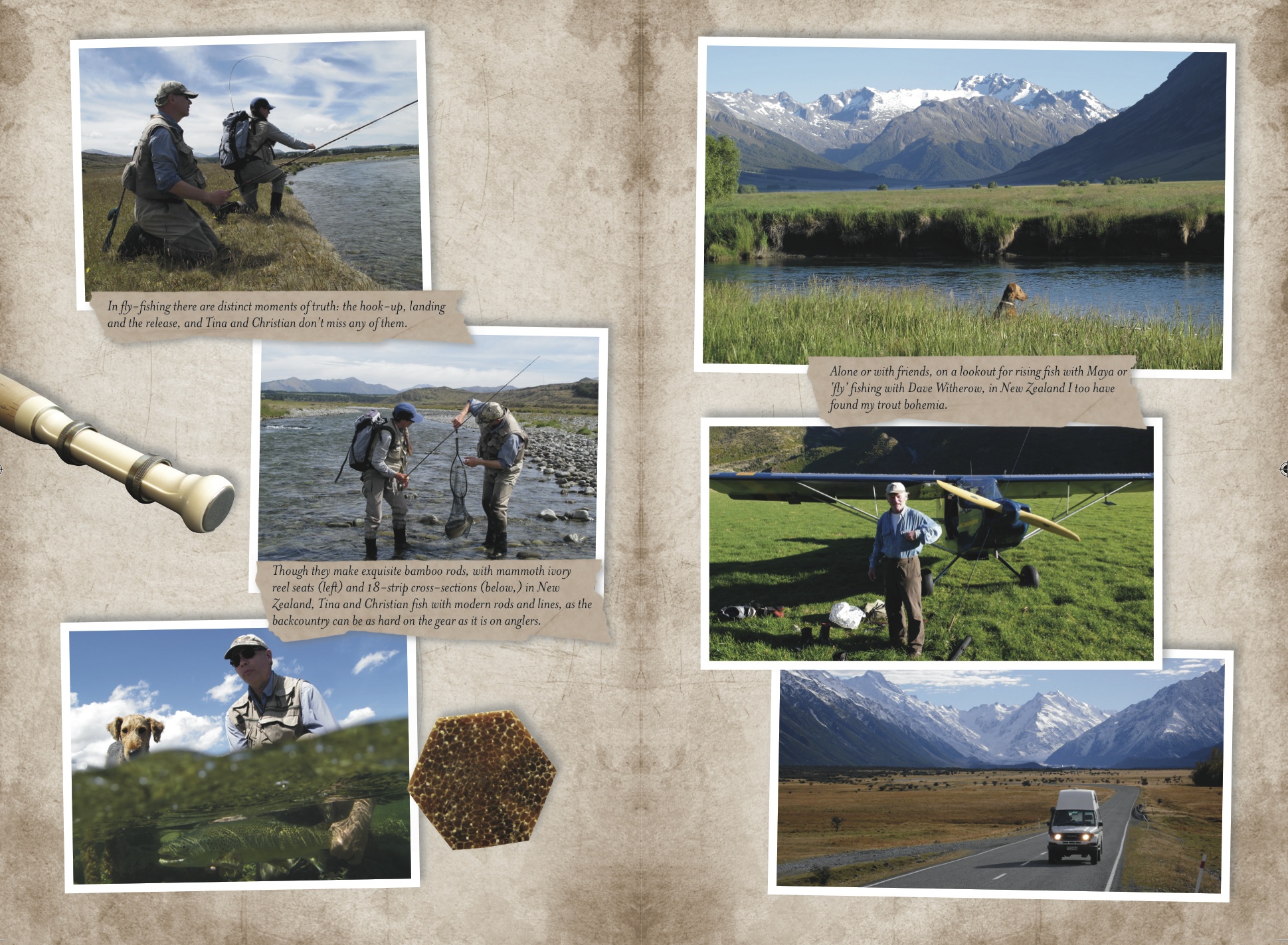

I’ve made new river friends since the Diaries, although perhaps making friends is not the right way to put it. It is almost always more an act of recognition upon meeting, as if we already knew each other well, just never had a chance to meet before. Years ago, I felt the same way when I fly-fished for the first time: it was not so much I got interested in it, or hooked, or fascinated by it in some way or another. It was a dawning of recognition, beyond doubts and need to question anything: here was something I would be doing for the rest of my life. Maybe we are born as fly-fishermen or women, and it just takes us varying amounts of time to find out who we are.

When you encounter such a river friend there is an instant compatibility and much of it is beyond words. You can fish together as if you’ve done it many times before, in companionable silence, for similar reasons and with a concordant reverence for the trout and the wild and natural places where the fish live. This togetherness on a river somehow magnifies the experience of fishing, takes it to a level of intensity that is rarely achievable alone. There is a loose and unassociated tribe of people from which most of my river friends come and of whom I’ve come to think of as the trout bohemians because of their lifestyle choices and attitudes, propensity for nomadic existence and the incomparable delight they derive from it.

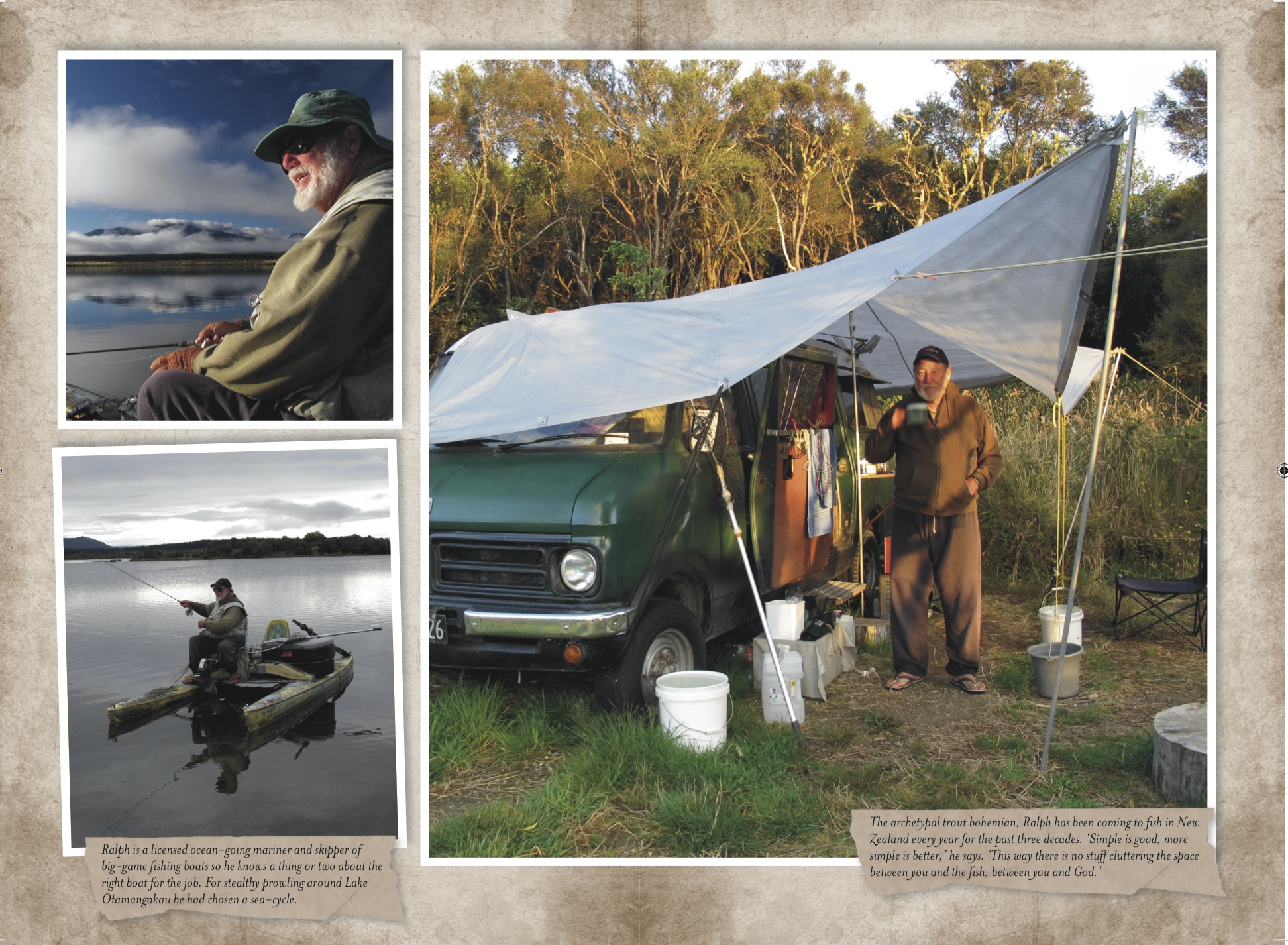

A common term for them would be trout bums, but to me such labelling seems trite and unjust, like calling a top brain surgeon a quack. Most of them are not bums at all. They are retired businessmen, academics on sabbaticals and off-season professional guides. I know a doctor, an aircraft engineer, a former punk rocker, a radiologist, a lawyer, a sea captain, a master-craftsman and antique dealers.

They are educated, well travelled and well read, often financially independent, versed in the ways of the world and a host of other subjects. Some would make exemplary Renaissance men and women. Certainly, then, not bums. What they do have in common, though, is that their lives and their priorities, at least for large parts of the year, have been devoted to the unwavering passion for trout. Theirs is the highest level of fly-fishing skills you’ll see anywhere, yet they are often obsessive about refining them further. They share an unquenchable thirst for being with the rivers and for being in the wild often for weeks at a time, coming into towns only to resupply and do the laundry. At times, the pursuit of trout seems but an excuse for such a lifestyle.

The trout bohemians have priorities different from those of most other people, and often a different set of values, which can be at odds with those of the society. By definition, bohemianism is unconventional and nonconformist, and might even be seen

as an escape from reality, if not a subscription to a different kind of reality altogether. But I’ll ask you: in the world which revels in disaster and strife, where wars are made into infotainment, consumerism into a state religion, and where the only news that sells is bad news, isn’t this sidetracking into the solitude of Nature and deliberate simplicity an attractive proposition?

Some of the trout bohemians are locals who had long ago realised what an amazing country they live in; others come from overseas, the way artists and writers flocked to the 1930s Paris, to indulge their passion, gypsy lifestyle and to find kindred spirits. They could go anywhere — to Alaska, Patagonia or Kamchatka — but they come here, to the Country of Trout, to what the Nelson guide Zane Mirfin called the ‘last best place’. Which is why I’ve come to think of New Zealand as the Trout Bohemia.

I crossed the last bridge and my heart skipped a beat. The butterflies in the stomach alighted again and would not settle. I was back on my river. It meandered in easy oxbows up the long wide valley, the willows lining its banks fresh with a green haze of new leaves.

I drove upstream to reacquaint myself with the waters. I saw no parked cars, no other fly-fishers anywhere. Coming here had always felt to me like entering a rustic idyll, decades behind the rest of the world. Over the years, I fished all the beats on the river, many times over, and so a day’s fishing here is for me as much alive with memories at it is with new possibilities.

Here is the place where, one evening, using a natural silk fly line I borrowed from Grandpa Trout, I caught a superb fish caddising along the high bank, while Grandpa solemnly waited for the mayfly hatch that never arose. Further up was the feed line tight against the trailing willow branches where I was spooled by a giant trout which took my dry fly with exquisite restraint then, realising his mistake, just kept moving upstream, never running or jumping but never stopping either, pulling steadily like a draught horse, until I ran out of room to follow, ran out of the line and backing as well, until it all went slack and all I had to reel in was the algae- covered piece of a sunken willow branch.

On this river, too, I had seen the biggest mayfly hatch ever, one which could have been a highlight of any fly-fishing life but which for me turned into a pinnacle of frustration. I was guiding a lovely and enthusiastic couple who, despite their apparent passion, money, and general bon-vivant attitude for acquiring all the good experiences, dry-fly trout included, never quite cared enough to iron the kinks out their casting, not to mention taking in anything I told them about drag-free presentation.

The mega-hatch lasted for over an hour and for half of it we were fishing to one particular trout while the waters around us were literally boiling with rises. My man was casting with the vehemence of a roulette player, throw-and-hope style, his desire to engage with the trout overpowering his attention to the cast and so my dainty mayfly imitations landed anywhere, from right at our feet, on my hat and backpack, to the willow branches above the fish. All this time the trout fed voraciously, taking, it seemed, everything that floated by. Except the man’s fly.

After a while an unspoken conviction must have grown in the man’s mind: I didn’t really know what the right fly was or didn’t have the right one for the job. Finally, he voiced it.

‘He won’t take the bug,’ he said, his hands unfolding open- palmed into the ‘what’s wrong’ gesture.

‘Fussy, i’nt he?’ I said, then, drawing on all the diplomacy I could muster, added: ‘Let’s go and find another fish.’

I just didn’t have the heart to tell him the simple and honest truth, lest it may have offended. ‘He won’t take the bug? Too right. He hasn’t seen it yet.’

The rise eventually petered out and we went back to the motel fishless and silent. That night, by mistake or from frustration, my clients forgot to turn off their outside light. When I came back in the morning to pick them up again, the porch floor was carpeted with dead brown #16 mayflies so thick you could barely see the grey concrete beneath them. I cleared the porch, sweeping it with a broom, the way a concierge would clear the house entrance after the night’s snowfall. There were so many mayflies they could have filled a bucket. I’ve never seen anything like this before or since.

I crossed the last bridge and my heart skipped a beat. The butterflies in the stomach alighted again and would not settle. I was back on my river.

My river of memories and promise. Two-thirds of the way up the valley I turned off the road, and through a farm gate — latched but never locked — bounced down half a mile of paddocks to another gate beyond which there were the river gravels. The farmers here are an exceptionally friendly lot. They still favour sheep over dairy cows — which in New Zealand have now become the antithesis of clean water and the bête noire of the fly-fisher — and most of them are aware of the treasure that flows beyond their fields.

There is usually a fence between stock and the river, often an electric one and packing a solid wallop of current (I know this from direct experience) and so the sheep you see near the water are only the long-ago escapees, shaggy and wild-looking, which had evaded repeated attempts at capture and live in the no-man’s-land between the farms and the river, in the impenetrable safety of the willow thicket.

I parked the camper in the shade, let out the dog, and went through the ritual of rigging up. The water is always cold here, the fish spirited, plentiful and hard to catch. A decade ago, when I first stumbled across this river I could not touch a fish for several days. It was just too hard. I stalked the banks, seeing a good number of trout, but I was unable to engage. My casts, flies, indicator, even my shadow or the shadow of my fly line, were forever spooking fish, so each day was like a long bad-luck story with many episodes compounding the effect. But I persevered because, back then, just as it is now, this seemed worth doing, a higher challenge requiring me to lift my game.

It did not come easy, but I experimented, and pondered, and drew conclusions, then discarded them and sought better ones. It was a fascinating process, a seesaw of despair and hope. Halfway through that first week I hooked my first fish here, on a single Swannundaze caddis nymph, on an extra-long and fine tippet and with no indicator, and it was an electrifying experience, if a surprise for us both. The fish threw the hook on one of its aerial somersaults, landing with a heavy splash, creating a momentary crater of white water, the line pinging back like a released rubber cord, all of this leaving me — still on my knees from the cast — trembling and in awe.

Maybe it was here that my journey of refinement began, and I’m happy that it did because good fly-fishing is largely about refinement, a progression from crude to exquisite. And maybe, a thought occurred to me as I was pulling on my waders, maybe my stalemate with Ella was a similar scenario, of skills thought considerable but proving inadequate. Maybe, I thought, she was like a river that was too hard at first but which, as its mysteries and idiosyncrasies were glimpsed and fathomed, had the power and depth to claim the most treasured place in the heart.

Maybe.

I locked Maya in the camper — this was sheep country in the middle of lambing — and approached the river. There was a tinge of snow-melt in the water, but I could see into it well enough. Just up ahead was one of the best pools and, sure enough, as my eyes sharpened and the mind switched into its hunter mode, calm but alert, I immediately saw several dark smudges on the shelf where the riffle emptied into the pool. They were the colour of deep water, dark green, almost black against the golden gravel. They looked like parts of the river bed, but as I watched one of them swung across briefly, then instantly returned to its previous position. A nymphing trout.

I unhooked a tungsten-bead nymph from the rod guide-ring, essed the loose line past the rod tip and thought that, considering the fast and broken water of the riffle where I’d cast, I could probably get away with a small yarn indicator. It was always so satisfying to see the tuft of fibres, floating down innocently like a lost feather, suddenly dip under and vanish, a visual cue of imminent action, like a sharp intake of breath.

High above, invisible against the watery-blue spring sky, a skylark was chirruping its breathless song, and ahead I had miles of river to fish.

It was good to be back.

SIGNED COPIES of THE TROUT BOHEMIA are available in my online bookshop here. Worldwide shipping.